The History of the Declaration of Independence

NATIONAL HYMN: George W. Warren composed the hymn tune NATIONAL HYMN specifically for the lyrics of "God of Our Fathers" for it to be used in the centennial celebration of the adoption of the United States Constitution. It has always begun with the trumpet fanfare, which sets the martial tone. Enjoy it while you read.

DISCOVER THE ORIGINAL COPIES OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

It was in August of 1775, a proclamation

so declared that the colonists, still being the King’s subjects were

engaged in an open and affirmed rebellion. Parliament in 1775 passed

the American Prohibitory Act, making all American vessels and their

cargo forfeit to the Kind. The colonists watching the events coming from

England became convinced the King treated the colonies a separate entity

from its mother land. Each colony slowing began to cut their ties to

England through the Continental Congress, whereby in March of 1776 they

passed the Privateering Resolution, allowing colonists “to fit out armed

vessels to cruise on the enemies of these United Colonies”. The

colonists open their ports to foreign trade and commerce with other

nations, severing ties of the Navigation Act, on May the 10th,

1776, the Resolution for the Formation of Local Governments was

passed. The colonists were on their way to independence.

The colonists

were slowly being convinced independence be the rightful conclusion.

Thomas Paine wrote and had published in January of 1776, Common Sense

and sold thousands of copies. By May of 1776, there were at least eight

colonies supporting the idea of declaring independence. The Virginia

Convention on May 15th of 1776 passed a resolution so stating

“the delegates appointed to represent this colony in General Congress be

instructed to propose to that respectable body to declare the United

Colonies free and independent states.” Richard Lee on June 7th ,

1776 presented his resolution, there were some colonies that supported

resolving their differences with England postponing a vote on Lee’s

resolution. On June 11th it was considered in the Continental

Congress, a vote of seven to five, New York abstained; postponed the

vote as congress was recessing. Since it they assumed the resolution

would pass, a committee of five being then appointed to draft a

statement, declaring independence.

The Committee of Five, consisted of John Adams of Massachusetts, Robert

Livingston of New York, Roger Sherman of Connecticut,

Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. In

Jefferson’s words from his writings in 1823, Jefferson wrote,

"unanimously pressed on myself alone to undertake the draught [sic]. I

consented; I drew it; but before I reported it to the committee I

communicated it separately to Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams requesting

their corrections. . . I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the

committee, and from them, unaltered to the Congress." John

Adams was later asked why he did not write the document and what why he

told Jefferson to author it; his answer: "Reason first, you are a

Virginian, and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business.

Reason second, I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular. You are very

much otherwise. Reason third, you can write ten times better than I

can." Jefferson on June 11th 1776 set out to

write the declaration.

Jefferson sat in his room at the room house where he lived, the weather

was hot; his lap desk set in front of him, with no books or writings

before him, only his knowledge retained through his extensive readings

he set his pen to paper. According to records, Jefferson formed on

draught which he presented to Adams and Franklin for review, changes

were made upon the document and he then rewrote it with changes which

was then presented to the Continental Congress on July 1st,

1776. It was at this time Congress met again after a three-week recess,

Lee’s resolution was passed, 12 to 1, New York not voting; Congress then

immediately began its discussion of the declaration. Jefferson’s

document was submitted with the changes made by Adam’s and Franklin, the

Congress then made additions and deletions; upon the morning of July 4th ,

1776 the Declaration of Independence was officially adopted, whereas the

church bells rang out signifying the adoption. From what we can surmise

through writings and documents existing, Jefferson wrote upon the his

copy, with alterations by Adams and Franklin in Jefferson’s hand,

bracketed phrases are those deleted by Congress, this was labeled ‘Rough

Draft’ by Jefferson, such remained in Jefferson’s papers till his death.

Sometime before it was adopted, Jefferson set a copy of the declaration

without Congress’ changes to Richard Henry Lee and George Wythe, these

copies exist in archival libraries at the American Philosophical Society

and in the Emmet Collection of the New York Public Library, another copy

resides in the Washburn Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society,

being sent to either John Page or Edmund Pendleton by Jefferson. In 1783

Jefferson sent to Madison a copy made from his notes of the debates in

Congress, Jefferson kept a draft of the Madison copy in his papers, John

Adams made a copy of the draft before submitting to Congress, surviving

today in the Massachusetts Historical Society.

The final draft taken to John Dunlap, a Philadelphia printer, also being

the official printer for the Continental Congress, it is perhaps what

many believe was the ‘fair copy’ of the rough draft but it is not proven

what copy was given to Dunlap, it is known the rough draft with Adams

and Franklin changes did survive; however the draft with changes made by

Congress did not. The Dunlap copies delivered to Congress,

then dispatched to assemblies, conventions, committees and Commanders,

Congress keeping one for their journal approving it of July 4th. No

one knows for sure just how many John Dunlap printed however over time

only 26 known copies have surfaced, these are known as the ‘Dunlap

Broadside’. Each ends with, ‘signed by the Order and Behalf of the

Congress, John Hancock, President. Attest Charles Thomson Secretary’ and

measures 14 inches by 18 inches on what they call, chain laid paper of

Dutch origin, imported probably from England. ‘They are

not signed by other members of congress, there is said one broadside was

actually signed in pen by John Hancock and Charles Thomson, yet this has

not survived or ever been found. Broadsides were a method

of the time to spread word or news of an important event all people need

know, such Broadsides drawn up and printed then dispatched for public

viewing in colonies; therefore, the Dunlap Broadside was the reasonable,

common method of dispatching the news of the Declaration of

Independence.

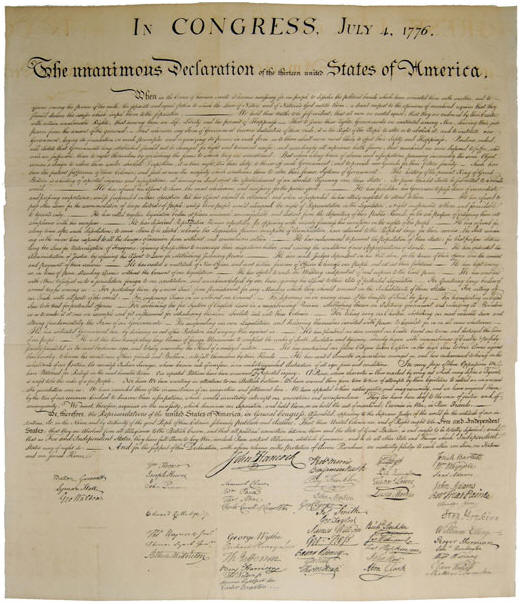

New York, on July 9th 1776 approved the

Congressional action, all 13 colonies now unanimously signified

approval. Congress ordered out an engrossed copy on July

19th. It was to have the title, ‘The unanimous declaration of

the thirteen United States of America. ‘ Once finished,

the engrossed copy, be signed by all members of the Continental

Congress. The engrossing process is one of preparing an official

document in large, clear pen, to which Timothy Matlack was most likely

the engrosser of our Declaration of Independence. It is known, Matlack

worked with Charles Thomson, secretary to the Congress; and had, in

fact, written George Washington’s commission to the Continental Army, no

doubt it was he that then penned the declaration. The engrossed copy was

24 ½ by 29 ¾ inches on parchment.

On August 2nd 1776, the Declaration of

Independence, having been engrossed, was set out to be signed. John

Hancock being the President of the Congress, was first to sign the

document, followed by to the right of Hancock’s bold signature at the

center, the signatures were so arranged by each colony the signers

resided, northern colonies first to the southern colonies last. Not all

signers signed on August 2nd, Elbridge Gerry, Lewis Morris,

Thomas McKean, Oliver Wolcott and Matthew Thornton, the latter was

unable to sign with his fellow New Hampshire delegates. According to the

July 19th order by Congress, instructing the

engrossed copy, ‘be signed by every member of Congress’, not all did

sign it. John Dickinson insisted reconciliation was still a viable

solution and Robert Livingston thought the declaration was being too

hasty, he was also on the committee of five to draft the declaration.

After the signing, the document was filed with Thomson, the secretary

for the Congress, on December 12th 1776,

threatened by the British, Congress moved to Baltimore, MD and

reconvened 8 days later. The Declaration rolled, moved with them by

wagon with other important and necessary articles. While

in Baltimore, on January 18, 1777, Congress, confident of the successes

at Trenton and Princeton, ordered a second official printing of the

declaration. The first printing, the Dunlap Broadside, had only John

Hancock and Charles Thomson names, mostly due to secrecy and security

for the delegates that did sign it; the second printing was to have all

signatures affixed. This copy is known as the Katherine Goddard from

Baltimore, caused 13 copies printed; the copy was

done in Caslon font, on cotton-rag paper, laid out in two columns,

measuring 16 by 21 inches. It stayed there until March of

1777 when it was returned to Philadelphia. On September 27th the

declaration moved again to Lancaster, PA, for one day, then moved to the

courthouse at York, PA from September 30th to

June of 1778. From there it moved and stayed at Philadelphia from July

of 1778 to June of 1783, whereupon in 1783 it moved to Princeton, NJ

from that June to November. After the signing of the Treaty of Paris,

the declaration moved again to Annapolis, MD, staying there until

October of 1784. It moved to Trenton, again, for the months of November

and December of 1784 where it moved to New York in 1785 where Congress

convened, being then stored at the New York City Hall and did so remain

until 1790.

During its course of stay at New York, secretary to the Congress,

Charles Thomson retired and surrendered his duties and the declaration

to Roger Alden, Deputy Secretary of Foreign Affairs. In September 1789,

the name of the department was changes to Department of State. Thomas

Jefferson being appointed the first Secretary of the State, returned

home from France to assume this duty, the duties of the Secretary of

State included the custody of the Declaration.

In July of 1790, Congress provided a new permanent capital of the new

nation be built, the chosen location was along the Potomac River, now

Washington D.C; meanwhile Congress moved to Philadelphia, whereas, the

declaration returned also, being then housed in several locations within

Philadelphia.

When in 1800, by direction of John Adams, then President, the

Declaration moved from Philadelphia to the newly built federal capital,

along with other government records of the time. The Declaration then

went on its longest trip upon water, leaving Philadelphia down the

Delaware River into the Bay, to the Atlantic Ocean, reaching the

Chesapeake Bay and up the Potomac River to Washington. The Declaration

was housed in the building used for the Treasury Department; it stayed

there for about 2 months then moved to one building of seven along

Pennsylvania Avenue, until moved to Seventeenth Street at the War Office

Building.

In August of 1814, being at war with England [War of 1812], seeing a

British fleet in the Bay, then Secretary of State, James Monroe,

observed the imminent threat to the capital city; and in doing so,

directed clerk, Stephen Pleasonton, causing linen purchased be made into

bags whereas all precious records including the Declaration, then put

upon carts, be then taken up the Potomac River and to an empty gristmill

owned by Edgar Patterson. Farmers, giving up their wagons for the use of

moving the precious documents to Leesburg, VA. While on August 24, as

the British attacked Washington, the Declaration and other documents

were traveling to Leesburg. The Declaration remained save in a private

home, where it stayed for weeks or until British troops left the area.

In September of 1814, the Declaration returned. It was moved only twice,

once for its trip back to Philadelphia for the centennial celebration

and during World War II when it was housed at Fort Knox for security,

now in Washington at the National Archives in Washington DC.

The Declaration of Independence many times had copies made; some

commissioned, others were not. Many done by express

permission of the government or commissioned by the government directly,

are found, sold or retained in collections of archival libraries of

universities, museums, historical societies or the government. The

original is the original, there is one engrossed Declaration of

independence, other copies done by permission or commission were limited

in the numbers, they are considered original copies. These

copies are known as the Dunlap Broadside [1776], the Katherine Goddard

{1777], the Binns Copy [1819],the Tyler Copy [1819],the Eleazer

Hunington copy [1820], the Stone copy [1823], the Peter

Force copy [1833 procured, inserted in 1848],the Anastatic Fac-Simile

copy (John Jay Smith) [1845], the London Peter Force copy [1855], the

Ohman lithograph copy [1942, 1955], and the Ira Corn copy [ 1974]. There

may be other copies, some with value, as original newspaper printings of

original time, have surfaced and other important printings. The copies

listed are among the most sought after and the most rare, all having

small numbers in existence.

Please note, we will not herein reference the value of rare, copies,

although rare original copies of the Declaration of Independence are

important, it is the words within the document need receive our highest

attention and reverence.

The History of the Original copies for the Declaration of Independence:

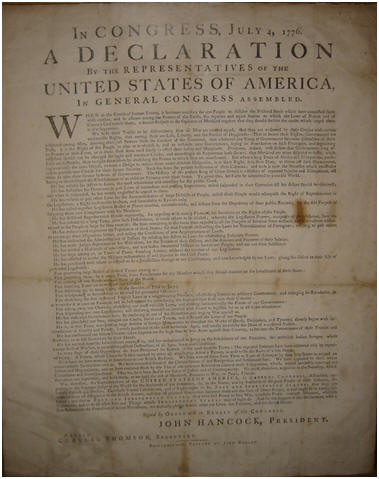

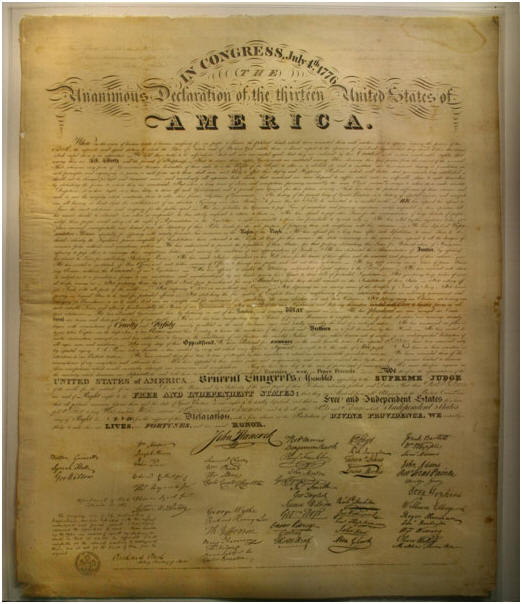

Original Dunlap Broadside

Emerging in the late

afternoon of July 4th, 1776, after twelve of the thirteen

colonies having reached an agreement declaring the colonies a free and

independent nation [New York held out], and being ordered by John

Hancock, President of the Congress to be authenticated and printed, the

draft of the Declaration made its way to John Dunlap, official printer

for the Congress.

Hancock’s order: “That the declaration be authenticated

and printed That the committee appointed to prepare the declaration

superintend and correct the press. That the copies of the declaration be

sent to the several assemblies, conventions and committees, or councils

of safety, and to the several commanding officers of the continental

troops, and that it be proclaimed in each of the United States, and at

the head of the army.”

Dunlap is thought to have printed about 200 copies, being

distributed to members of Congress, throughout the colonies, and to

England. George Washington upon receiving his read it to the troops,

boosting the morale of the army. John Hancock and Charles Thomson

signed two copies being sent to England, Hancock signed his name in bold

pen for the King but as far as we know or is noted in history, the Kind

never received that copy and no one knows what happened to them, no

signed copy of the Broadside has surfaced.

The Dunlap Broadside

varies slightly in size averaging 15 by 19 inches, printed on Dutch

chain laid paper, probably imported from England. Some of the copies in

existence vary in paper and size, some have been found to contain errors

yet others do not, causing one to surmise, as the printing began,

someone noticed the error, corrected the letters, and continued, those

printed after have a space where the lettering was adjusted. Dunlap was

ordered that the copies be made in haste, it is no wonder as they worked

through the night, errors were made, corrected and what paper of that

size being readily available, used.

Only 26 known Dunlap Broadsides exist today, perhaps there are others,

tucked away somewhere but until they are found; only 26 known to exist. They

are in public and private collections.

New Hampshire broadside

The New Hampshire broadside, contains no printer name or place, it is most likely printed after the arrival of the Dunlap Broadside to New Hampshire around July 12 or closely thereafter, in Exeter by Robert Luist Fowle. The copy as seen was that of Charles Toppan, a noted antiquarian, the first in producing Jefferson's manuscripts of the Declaration of Independence, his family inherited it. This particular photo was the sale of such copy by Seth Kaller auction house of historical documents and transcripts.

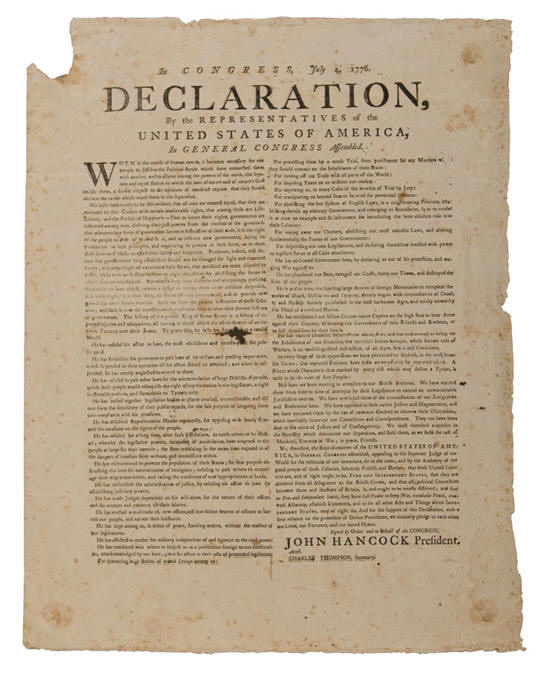

THE MASSACHUSETTS COPY

Massachusetts copy

This a broadside of the Declaration of Independence, like most colonies, the Dunlap Broadside caused others to be printed locally for distribution to the public whereas citizens could view it. Most colonies copies were printed near or about July and August of 1776. There is usually found, print at the bottom indicating where it was printed, who ordered it to be printed, and the name of the printer. They were printed on paper.

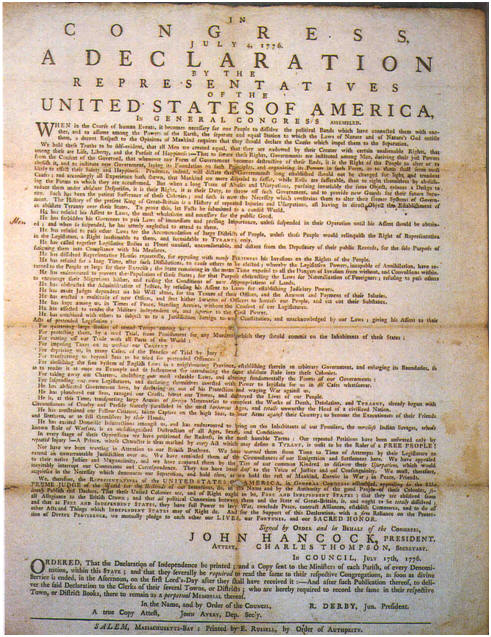

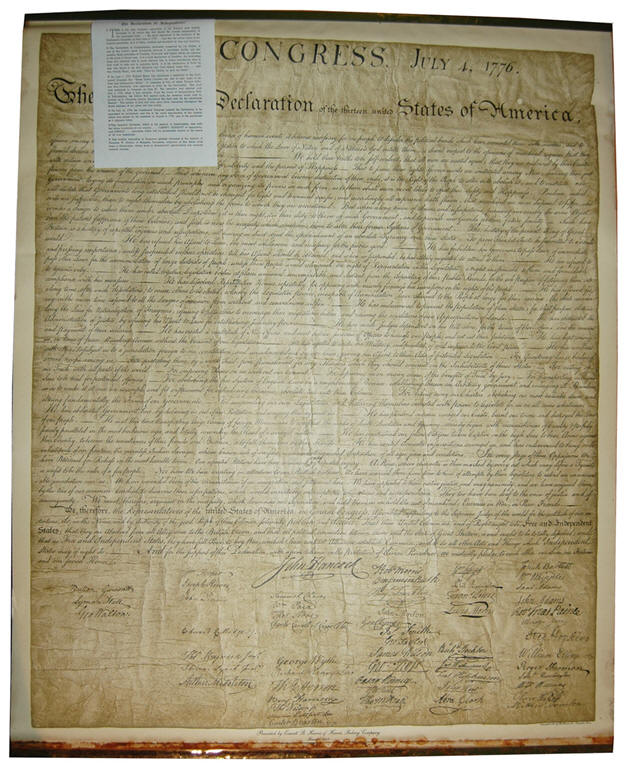

THE GODDARD COPY

Goddard Copy

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE - GODDARD PRINTING

(January 1777)

Approximately 16" x 21". The first printing to list

the names of the signees and the first printed in two columns. Marked at

bottom "Baltimore, in Maryland : Printed by Mary Katharine Goddard."It

was printed in Caslon font, on cotton-rag paper. Ordered by the Congress

as an official copy for the record. Postmaster/Printer Goddard set the

type from the original engrossed version and mailed one to each state so

people would know the signers. Until this time the signers, for security

reasons were unknown, the fear of the British discovering who signed it

could have put any of them in danger. With successes of the battles of

Trenton and Princeton Congress ordered the printing by Goddard in order

to reveal the signers, it is the only Broadside copy ever officially

produced containing all signers names. There is one name absent from the

print, that being, Thomas McKean, who signed the engrossed copy too late

for inclusion. Nine known copies to exist.

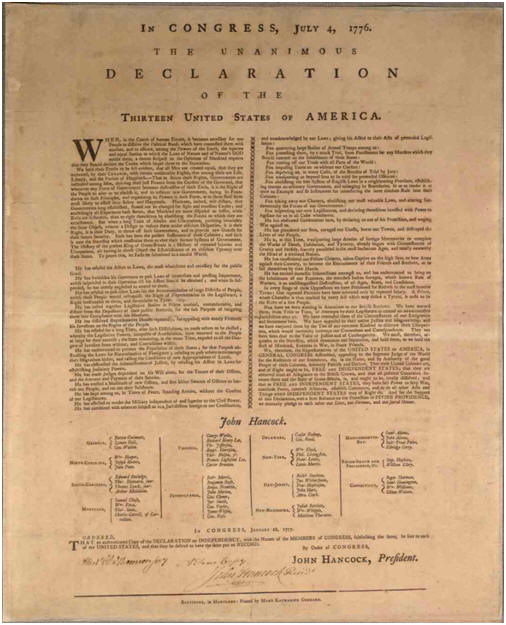

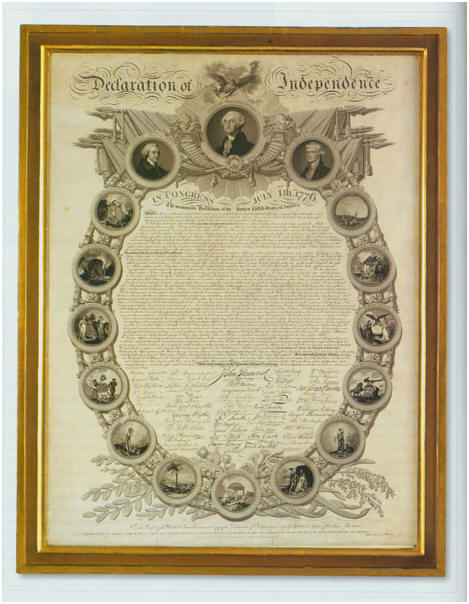

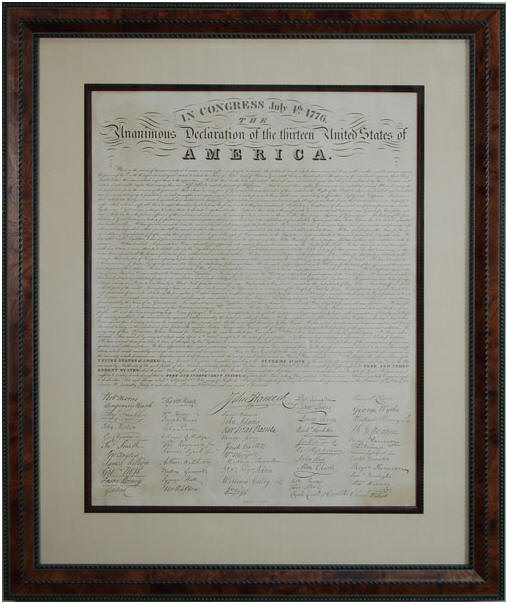

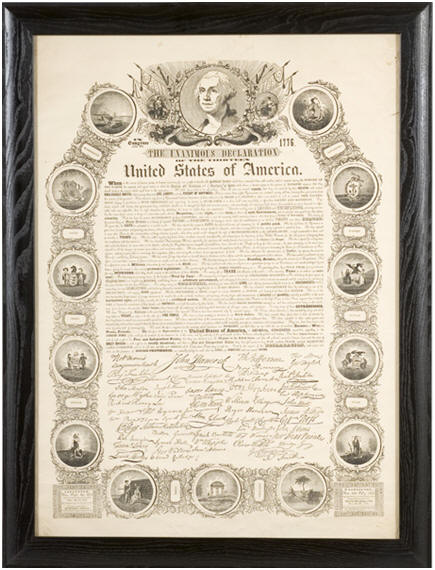

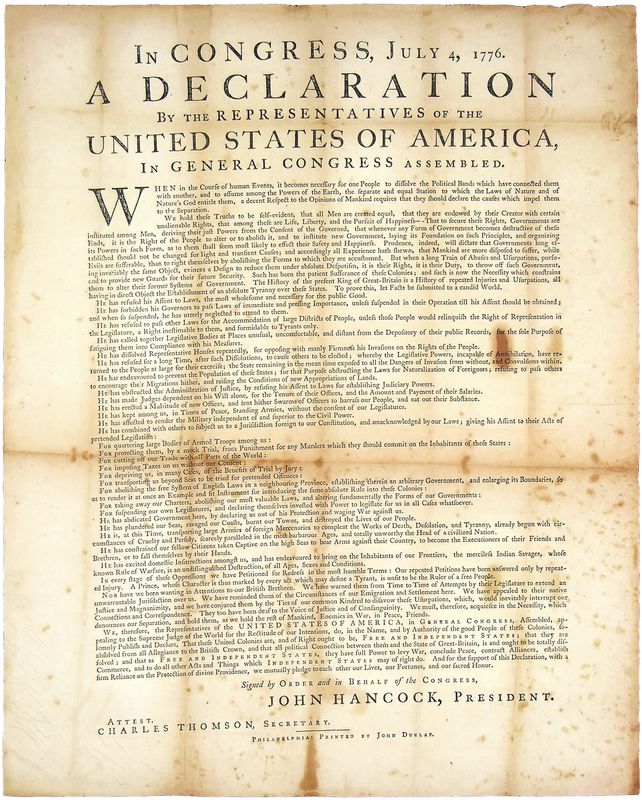

THE TYLER COPY

Tyler copy

Washington, 1818. Engraved by Peter Maverick. 31 x 27 inches. The title and text are in various ornamental scripts; the signatures are in facsimile. Produced on paper, a less amount on vellum and only about four known printed on linen or silk.

Until 1818 Americans never saw the writing of the Declaration, only being seen in print on Broadsides or Newspapers. Two rival printers, John Binns and Benjamin Own Tyler desired to be the first in publishing such a copy. Binns begain in June of 1816 taking subscriptions for his print of the Declaration which was to be surrounded by portraits and seals but he failed to produce the finished work until 1819. Meantime, Tyler, making full advantage of Binns publicity, set out creating a copy himself, unornamented, in April 1818; complete with facsimile signatures and dedicated to Jefferson. He asked permission to dedicate the engraving to him, Jefferson replied to him: ‘for the few of us remaining can vouch, I am sure, on behalf of those who have gone before us, that notwithstanding the lowering aspect of the day, no hand trembled on affixing its signature to that paper.’

Tyler sent Jefferson a copy on parchment and visited at Monticello around May of 1818, he spent the day teaching penmanship to Jefferson’s family. Jefferson’s prints of the Declaration of Independence being dispersed among his family after his death, have not survived.

THE WOODRUFF COPY

Wm Woodruff Copy

William Woodruff’s engraved copy of the Declaration of Independence

appeared just before the Binns copy. While Binns had

Hancock’s image, Woodruff used John Adams, the signatures rather than

facsimiles are calligraphic, and said to be near exact as the originals.

The engraving was printed several times, the first being in 1819, and

the last being about 1840. The printings were not all done by the same

printer, therefore when finding a Woodruff engraving there may be

several markings on the lower edge depicting the printer’s name and one

such printing had Woodruff’s signature; the different publishers:

‘published by Phelps & Ensign 7 ½ Bowery, N.Y.’ , Philad. Published Feb

20, 1819 By William Woodruff’ Some have ‘Wm Woodruff’ signature lower

right and bottom center Published 1819.

The Woodruff copy is 22 by 25 respectfully; the seals of the 13

colonies and images of the first 3 Presidents around the text.

To compete with Tyler, Binns opted for a more ornamental and artistic

production, putting in state seals of the original colonies forming an

oval with portraits of Hancock, Washington and Jefferson at the top. He

took great care using the best likenesses available to him. He could not

however gain a copyright until 1818 causing a delay in delivering this

print, as he had begun taking subscriptions for it in 1816. Compared

with Tyler’s Binns’ document was expensive, he charged ten for the

plain, and if colored, thirteen. His signatures did not

compare to Tyler’s, his being so good they were often mistaken for

genuine signatures of the signers; Binns’ could never be mistaken. John

Quincy Adams attested the signatures to be exact imitations and the

whole copy said to be a correct copy. Binns used five artists to

complete his work, the eagle at the top painted from live and dedicated

to the people of the United States. He listed his credits as:

“Originally designed by John Binns, ornamental part drawn by Geo.

Bridport, arms of the United States and the Thirteen States drawn from

official documents by Thomas Sully, Portrait of Gen’l Washington painted

in 1795 by Stuart, Portraits of Thomas Jefferson in 1816 by Otis,

Portrait of John Hancock painted in 1765 by Copley, Ornamental part,

arms of the United States and the Thirteen States engreaved by Geo.

Murry, the writing designed and engraved by C.H. Parker, Portraits

engraved by J.B. Longacre, Printed by James Porter.”

The Binns print measures 24 by 35.5 inches. Binns had hoped to sell 200 copies of his print to the government but was disappointed in 1820 by then Secretary of state John Quincy Adams's commission of an exact facsimile of the original by William J. Stone. When completed in 1823 Stone's print was considered the "official" copy for government use.

THE HUNTINGTON COPY

Eleazer Huntington copy

Eleazer Huntington’s copy is believed to be printed in Hartford,

Connecticut at or near 1820 to 1824. The print measures 21.5 by 25

inches, imitating Tyler’s print but in a smaller size. The design while

mimicking Tyler’s design, Huntington lacks some of the details but

remains an excellent engraving.

Huntington copies

were often hung in schoolhouses therefore originally hung on wooden

rods, when such copies are found today flaws are often seen considering

where they had been hung and the exposure to harm was high. When found,

they can be quite valuable.

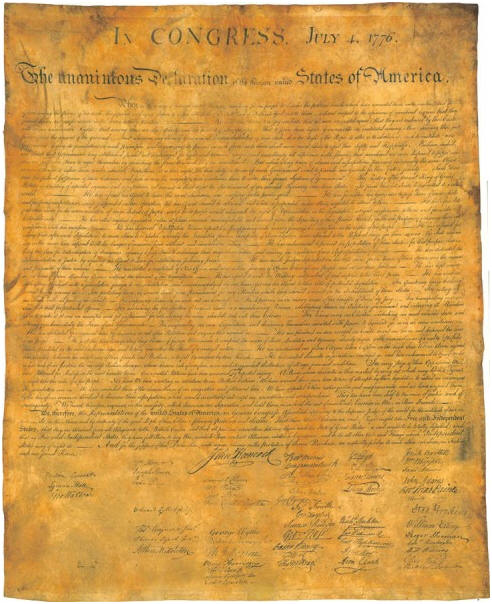

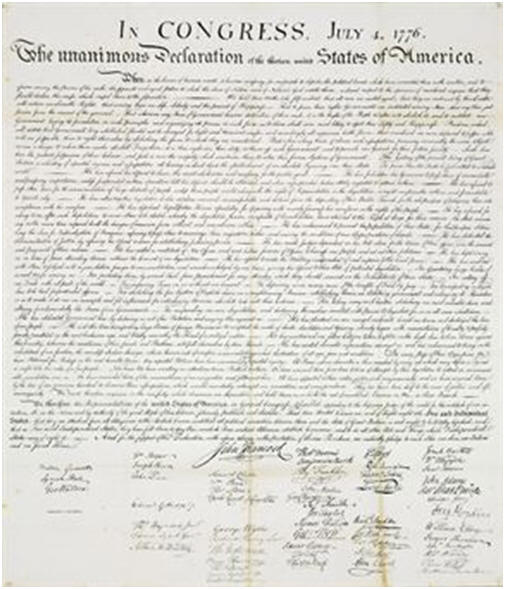

William Stone was commissioned in 1820 to make the first full-scale exact replica of the Declaration of Independence. After three years producing the copper plate, in 1823 Congress ordered 200 copies printed on vellum and distributed to the three surviving signers, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams and Charles Carroll, also to President Monroe and Lafayette. The copy measures: 33 ¾ x 27 ¼ inches .

The Declaration of Independence in 1820 was then housed at the National Archives in Washington, DC, it was already deteriorated, this would provide an exact copy on a copper plate. Many debate if Stone’s process called the ‘wet’ process caused further damage to the document; however recent discoveries show it was not Stone’s process but another copying process later done. Of the 200 copies made only about 40 are known to exist, of those 21 are in public collections, while the others in private collections. There were subsequent facsimiles done from the copper plate however the ways to distinguish the first printing with subsequent printing is Stone’s original imprint on the top left reading: ‘Engraved by W.J.STONE for the Dept. of State by order,’ and continuing at top right: ‘J.Q Adams, Sec of State July 4, 1823.’ After this first edition the engraving at the top was removed, replaced with a shorter imprint at the bottom left reading: ‘W.J.STONE SC WASHn,’ this shorter imprint is seen on subsequent plates and prints. The Stone copy illustrated is a later copy with the shorter imprint.

THE MORRISON COPY

Morrison copy

This Broadside copy was printed by C. A. Elliott, Philadelphia, PA, published by Thomas Morrison of Philadelphia in 1832 [copyright: Dec. 8th 1832]. It is very ornate with a central medallion bust of George Washington with spread winged eagles to either side, printed text of the Declaration of Independence with printed signatures of the signer. Also you find 27 states with populations and principal towns hand colored in red , green and yellow. The document is 27 by 20 inches. A wonderful artful broadside.

THE PHELPS COPY

Phelps copy

The Humphrey Phelps copy is of a broadside style, much like the Binns copy, published in 1845. It gives tribute to Washington and LaFayette at the lower corners, often you will find this copy colored. It was published in New York.

PETER FORCE COPY

Peter Force copy

On July 21st, 1833, the original engraver, William Stone, invoiced Peter Force for 4,000 copies of the Declaration of Independence, Force must have assumed he would sell at least 2,500 copies of his American Archives, 1500 being commissioned by John Quincy Adams. Peter Force was a noted archivist and historian compiling the American Archives, originally planned as a series of more than twenty volumes, with the most important original materials from American history, from the 17th and 18th centuries. The project was abruptly cancelled by Secretary of State William Marcy, leaving Force in debt; ultimately causing him to sell his massive collection to the Library of Congress for $100,000, to replace books lost in a fire at the Library of Congress.

The American Archives were not printed until 1848 some 15 years after Force procured the copies from Stone. After mounting expenses and increasing delays in producing Series IV, by 1843, when Force was re-authorized by Congress, he had by then scaled back his subscription plan to only 500 copies.

The Force printing, the second edition of Stone’s facsimile, remains one of the best representations of the Declaration of Independence, his imprints that never were folded for inclusion in books were never protected and are very rare, the folded copies are the mostly likely found today. All though are rare to find, and no one knows exactly how many Force copies ultimately circulated. The copies are of the Stone measures: 33 3/4 x 27 1/4 inches.

In addition to his work on the Archives, Force made some other contributions to American history. He was the first scholar to discover that the so-called Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence of 1775 was not what it purported to be. Then he published The Declaration of Independence, or Notes on Lord Mahon's History of the American Declaration of Independence (London, 1855 ). Occasionally, too, he printed a paper on a subject not directly related to his field: in 1852, Grinnell Land: Remarks on the English Maps of Arctic Discoveries, in 1850 and 1851; and in 1856, a "Record of Auroral Phenomena observed in the Higher Northern Latitudes" (Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Vol. VIII). These minor works perhaps are of interest merely to the antiquarian, but the American Archives are still indispensable to every student of the American Revolution.

Lingenfelter, discoverer of the Anastatic copy says,’The Anastatic Declaration is a facsimile from a plate produced by a chemical transfer process that nearly destroyed the original engrossed Declaration.’ This copy is not just a facsimile but its significance is by the fact this anastatic process itself was the one of the major causes for the original engrossed Declaration’s current condition.

The discovery that this

early American attempt at imaging using a process developed in Europe

and brought to this country by John Jay Smith as a commercial venture is

an exciting development in the history of the Declaration of

Independence. Proof of the use of the Declaration of Independence as an

original used for the anastatic process is offered by Edward Law, as he

has discovered a reference in the December 9, 1846 Alexander’s

Pictorial Messenger

announcing the availability of anastatic copies of the Declaration of

Independence and the Non Importation Act of 1765 from the Anastatic

printing office on Chestnut Street.

The absence of a printer’s name on the Anastatic Declaration suggests

that someone directly connected to the patent agent produced it.

An October 27, 1846 report on a Franklin Institute Exhibition in The

North American names John Jay Smith’s son, Lloyd P.

Smith as the printer of the Anastatic Declaration. There is a copy at

the American Philosophical Society and another in the collection of

Independence National Historical Park,” said Law. He believes that

the absence of a printer’s name on the Anastatic Declaration suggests

that Smith, the patent agent, produced it.

“Smith thought the Declaration would bring the anastatic process to the

attention of the public, it would brand his product. It was neither

commissioned nor endorsed by the Government, it was a business endeavor

and has a place in printing history,” said Chief Curator Karie Deithorn

in Philadelphia. “He looked on it as a perfect advertisement, a

marketing tool for his business venture, at a time when the Declaration

was not revered as a holy relic as it is today.” Deithhorn also alerted

Lingenfelter that she had in her files a newspaper clipping from the

July 7, 1846 (Philadelphia) Public Ledger reporting

a visit by Generals Houston and Rusk, then U.S. Senators, to the

Independence Hall. They noticed an “anastatic copy of the Declaration”

in the room with the Liberty Bell and called it “a perfect facsimile of

the original and an exceedingly appropriate ornament.”

Lingenfelter explains: “Until I showed the curators at Independence

National Historical Park my copy and told them what I had learned about

anastatic printing, they assumed the copy in their collection was merely

a Centennial souvenir from 1876.” The park put that copy through a

conservation process in the 1980’s and it has remained in archival

storage since that time.

It is difficult to believe that Smith produced only two Anastatic

Declarations, but the Independence National Historic Park and

Lingenfelter documents are the only two known copies.

Until now, scholars were unaware of anastatic printing and its relation

to the condition of the original engrossed Declaration.

Previously, the damage to the document was thought to be only due to

constant exposure of the document to sunlight when it was on display in

a government office building. Some attempts have been made to cast blame

upon William Stone, intimating that certain damage may have occurred

during his time with the document.

The fact that the original would have been exposed to the harsh

chemicals involved in the anastatic process would be considered

blasphemy if suggested today, but in 1846 there was not the respect for

the original document we hold today. That the original document was

exposed to such a new and potentially risky process – and the ultimate

results – may explain why those who had access to the document made no

mention of their attempts.

Edward Law’s great interest in the propagation of the anastatic process

led him to become one of the world’s experts in its processes and usage

in that age. Law points to an 1891 auction catalog for “Revolutionary

Documents, letters and relics of George Washington and Scarce American

Maps and other rarities,” cataloged and conducted by

Stan V. Henkels, for Thos Birch’s Sons auctioneers, 1110 Chestnut

Street.

It describes as lot

709 The Declaration of Independence, an Anastatic Copy

on parchment from the original, as to make this they allowed the

original document to be placed under a certain process, which enabled

the projectors of the scheme to take a…facsimile…from the original. That

this outrage was perpetrated the original Declaration too clearly shows

as it is so faded as to be hardly discernable to the naked eye…and from

which they were enabled to take a few impressions…this, therefore,

really portrays more truthfully what the document was than the original

itself.” Lingenfelter believes this may be the very

copy in his possession, although his is on paper not parchment.

Lingenfelter explains that auctioneers often confused paper and

parchment, and that printers did not use real parchment in the 19th century.

The Buttre copy

This copy is produced in the broadside manner, in 1856, of approximately 16 by 20 inches, hand colored and marked ‘border drawn by W. Momburger – Lettering by C Craske – Engraved & Published by JC Buttre, 48 Franklin St. N.Y.’, with a copyright date below the 1856 mark. It was printed on hard card stock.

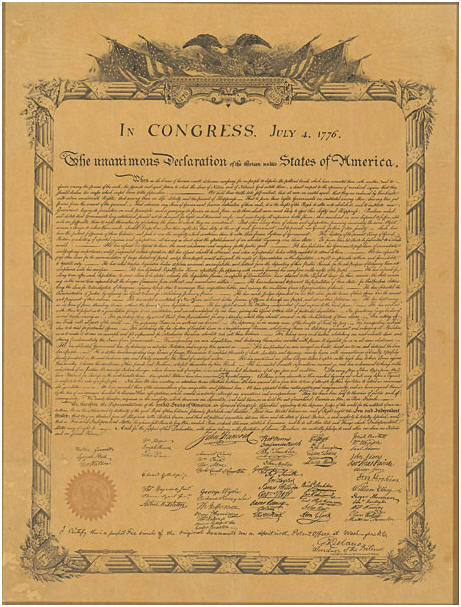

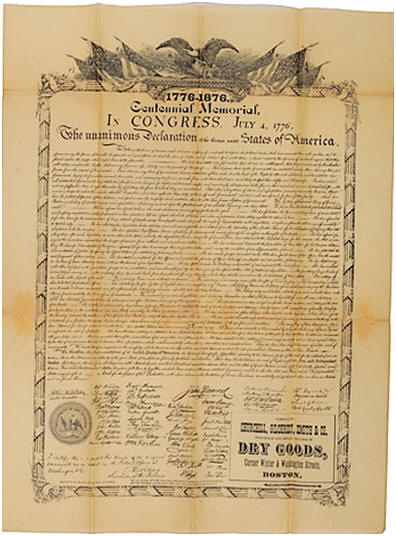

The centennial copy, ornately bordered with the bald eagle and American flags, was copy written in 1874-76 by James McBride, with a certification along the bottom in the hand of the interior secretary: I certify that this is a perfect fac-simile of the original document now on deposit in the Patent Office at Washington D. C./C. Delano/Secretary of the Interior, a seal of the Interior Department seal placed next to the statement. The copy is 24 by 32 inches. Printed at the bottom, a notice for sale of copies, ‘sending 1.00 to the Continental Publishing Co. Philadelphia, Pa. will receive post – paid in a rolled paper/case a copy of this Declaration on Steel Plate Paper 24 X32 inches’.

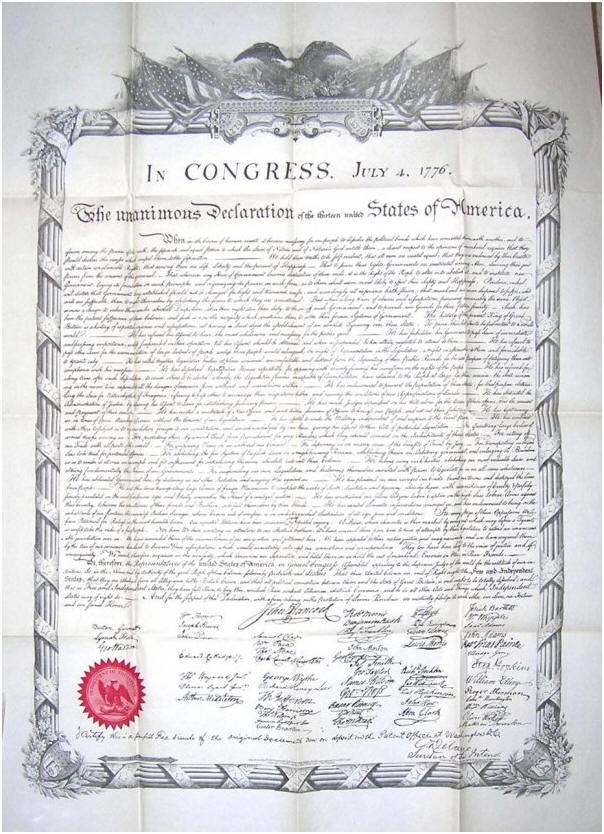

Centennial copy with no advertisement

1876 Declaration of Independence commemorating the Declaration's 100th

anniversary. Philadelphia: Parchment Publishing Company: 1876. Printed

on parchment-style paper and certified by the United States Secretary of

the Interior as a commemorative re-issue of the original document. Copy

of Declaration accurately reproduces original handwritten text and

roster of signatures. Document measures approximately 24'' x 32''.

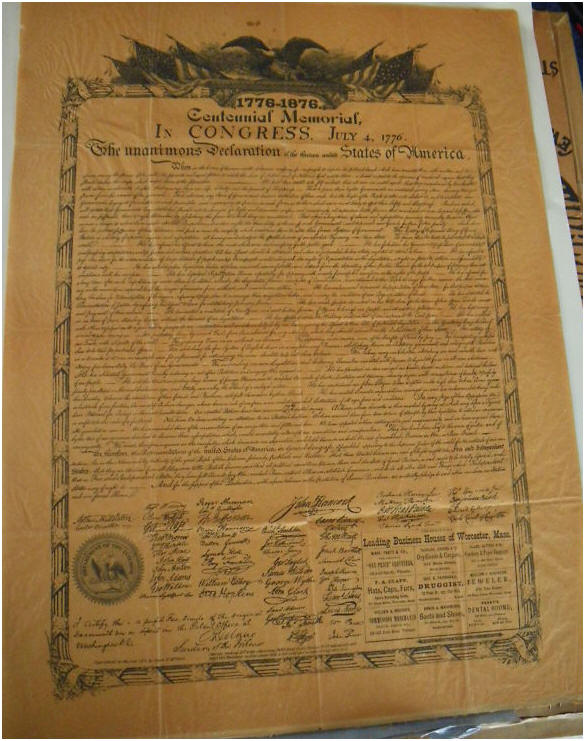

McBride Centennial Memorial copy

This copy is approximately 15 by 19 and in the lower right corner

advertises for local merchants in Worcester, Ma, it is contains the seal

on the left, the certification is below the seal, stating the Secretary

of the Interior certifies it to be an exact fac-simile of the original

in the US Patent Office. McBride copies found, each

with advertisements in the lower portion, all with seals and the

statement from the Secretary of the Interior, were not all printed by

the same printer, this particular copy was printed by Columbia

Printing company in Nassau New York.

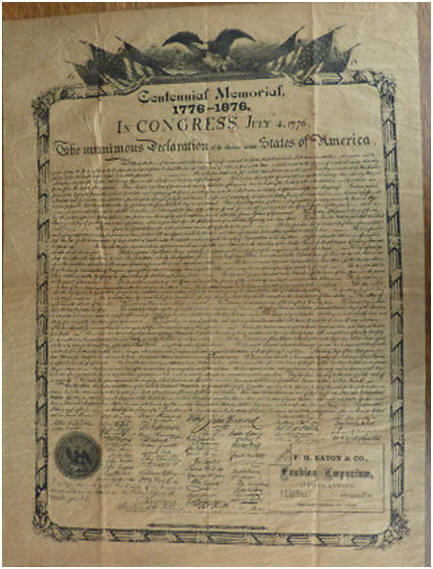

This copy printed

at Columbian Publishing Co. NY is 15 by 19, folded most likely for

mailing; you may observe the advertisement in the lower right corner

and the typical seal with certification.

All Centennial

copies are typically the same and on the top have Centennial

Memorial with the dates 1776 – 1876 adorned with the bald eagle and

flags, most will have an advertisement however there are some found

absent advertisements.

THEODORE OHMANS COPY

Theodore Ohman's copy

Theodore Ohman Declaration of Independence. In 1942 master lithographer Ohman created this reproduction DOI in a two-step process: the background is a photo taken of the actual Declaration. Superimposed over this is an image taken from an original Stone engraving of the Declaration. The result is a remarkably realistic copy of the document as it would appear if the original ink not faded. Measures 32.5" x 26" Most Ohman copies are sponsored by a company and bears the name on the document, you may find them by Coca-cola, Bakeries, industrial companies, etc.

Upon arriving in the United States, Ohman made a trip to the Library of

Congress to see the Constitution and the Declaration. Ohman was

horrified to learn that the Declaration had been permanently damaged in

1823 and the Constitution was in very fragile condition. After seeing

these marred and damaged originals, Ohman dedicated the remainder of his

life to re-creating both the Declaration and Constitution as they

originally appeared in 1776, so that people would always be able to

appreciate the two documents that made and keep us free.

Ohman realized that if he could obtain one of the original parchment

engravings, it would contain a more exact image of the original

Declaration than the now-damaged original itself. After an exhaustive

search, Ohman located one of the parchment copies made by Stone and

immediately purchased it from this, the text of the script and the

precise original signatures of the Founding Fathers were obtained for

reproduction. As luck would have it, Ohman also located a negative of

one of the last photographs taken of the original Declaration before it

was sealed in its permanent glass shrine in 1903. From this picture,

Ohman was able to reproduce the appearance of the cracked and smudged

original parchment.

IRA CORN COPY

Ira Corn Copy

This copy was recreated from an original Dunlap Broadside

printing. The Dunlap Broadside used is called the ‘Lost Copy’ as it was

discovered in 1968 on a bookshelf at Leary’s Book Store in Philadelphia

when the bookstore was closing after 132 years in business. The Lost

copy was purchased at auction by Corn and Discoll, Dallas business

executives for 404,000 in 1970. They first restored the document and

then commissioned R.R. Donnelly & Sons Company, The Lakeside Press to

produce a limited set of facsimiles. Every detail from the paper type to

the type of printing, being faithful to the original. Heavy Dutch chain

laid paper obtained from near the place of origin as Dunlap’s Dutch

paper, the printing was on a hand letter press with heavy impressions as

exact as possible to the original. There is a slight wrinkle in the

lower corner, as the original, the edges were die cut to the exact worn

edges of the Dunlap original, stains replicated, age marks made, all

exactly the original as it is today, even to the point of matching the

back to the original. The size is exactly as the original copied,

measuring 15 ½ by 19, varying the original due to age. There is a

statement on the back declaring it as a copy to prevent any future

confusion as to its exact age, and will authenticate it as a Ira Corn

Declaration.

The original Dunlap Broadside [Corn’s} was then acquired by the City of

Dallas where it is now housed. The facsimile copies were given to close

friends; however over time the remaining copies were forgotten, until

recently discovered, much like the original in a book store, still in

the Donnelly wrapper. Ironic how history repeats itself. It

is not known how many copies Ira Corn actually produced or how many

exist today.

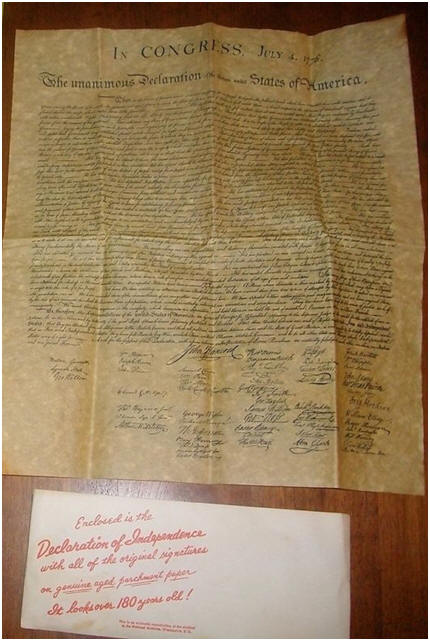

This copy is a small size, 15 ½ by 13 respectfully, and printed on aged vellum paper giving it an aged look. It is usually found folded in long rectangular folds so as to fit within a standard business size envelope. It is a good copy to display in your home or office giving it a sense of age, the size small for easy hanging.

We know there are other copies made; what we have listed are among the most sought after and significantly made their mark upon the history of the Declaration of Independence. Most colonies had their own broadsides and as we discover information in their regard we shall post for your viewing.

Please understand, the words of the Declaration of Independence are most sacred to citizens, those very words brought to us the birth of this nation, giving us the freedoms and liberties put forth in the Constitution. Our Founding Fathers, knew the importance of preserving the freedoms they fought for, the grievances bringing them to separate from Britain, gave cause for the articles and amendments within the Constitution preventing tyrannical power over citizens. The leaders of America are its citizens; our job as leaders is preventing elected officers authority for changing what we do not want or the Constitution does not allow.

Read the words of the Declaration of Independence, hang it on your wall as a sign and remembrance, that you are a citizen of a free America. If you find a copy or have a copy you think rare, research its size, style and paper, contact us if you need further assistance.